With nowhere else to turn, Juliet Sanomi started her own school for students on the spectrum

BY ROGER MOONEY

PLANTATION, Florida – Joshua Akabosu was nearly hit by a truck when he was 10.

He had run from school that day, as he often did. Announced to the class he was going home, then bolted through a door and into the neighboring streets.

An aide, whose job was to shadow Joshua throughout the school day, fractured her foot during the chase.

School officials told Joshua’s mom, Juliet Sanomi, what she already knew: that they could no longer accommodate her son. He was a flight risk and posed a danger to himself and others.

Joshua, now 20, is on the autism spectrum. He has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). At the time, he was just learning to speak in complete sentences.

“I took him to (his district) school, they couldn’t handle him. I took him to private schools, same thing,” Juliet said. “And no fault to the schools. These children don’t come with manuals.”

But where does a single mother turn when she has nowhere else to go? When homeschooling is not an option because she is pregnant, and because she wants her son to interact with other children?

In Juliet’s case, she turned to herself. She started her own school.

Dickens Sanomi Academy in Plantation is celebrating its 10th year. It has 170 students, most of whom receive the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA), which is managed by Step Up For Students.

Joshua graduates this spring. He was one of the original seven students during the school’s first year.

“I am very grateful for the (FES-UA) because it was difficult. He wasn’t asked to be born with autism and it’s been a difficult road,” Juliet said. “I thank God for the scholarship because he’s done very well, the best he’s able to do, and that’s because we had the funds to do that.”

Joshua was the school’s first student. The second student came through a chance meeting with the mother of an autistic child. The mother was standing in the parking lot outside of a school. She was crying because school officials just told her the same thing Juliet had recently been told about Joshua.

“I said, ‘Listen, I just started a school, and it is just my son. Do you want to come and join me?’ She said, ‘Yes,’” Juliet recalled.

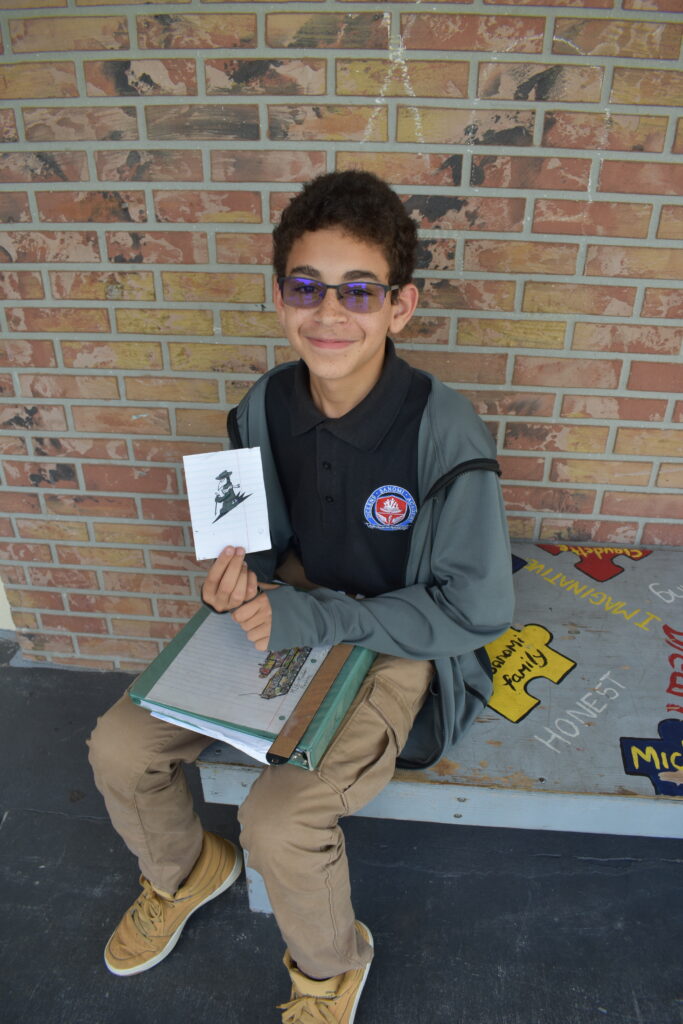

Five more students followed that year, including Isaac Wilbanks.

Isaac, now 15, had come with a thick file compiled at his previous school of all the times his mother had been notified because of his behavior.

“The teachers didn’t know how to manage Isaac’s behavior. He has a social behavior that needs to be worked on,” his mom, Herlie, said. “Every little thing he did was wrong.”

The administration at Dickens Sanomi does not have a file on Isaac.

“We don’t call the parents unless it’s something major,” Juliet said.

Herlie found Dickens Sanomi Academy on the Step Up website. She called Juliet, told her about Isaac and asked if the school could meet his needs. Juliet said yes, and Herlie didn’t waste any time enrolling her son. She knew almost immediately that Isaac was in the right school, because she stopped receiving emails about his behavior.

“The teachers take the time to get to know the students,” Herlie said. “They don’t make assumptions, and the students see them as mentors, as their leader.”

Isaac, who is gifted in science and art, is doing well at the school. A budding cartoonist, he is drawing “Turbo Forces,” an animated world of superheroes.

“They’re a group of heroes who deal with cataclysmic events,” he said. “Something breaks in the universe, and they have to go fix it.”

There are 13 teachers at the school, seven members of the support staff, seven therapists, and four members of the exceptional student education department.

It’s their job to know each student, and they do this by first earning the student’s trust, Juliet said. That forms the foundation of whatever that student is capable of learning.

“Now you see the child’s behavior change because they can tell you what they want,” Juliet said. “They don’t have to scream. They don’t have to yell. They don’t have to bang their head. If there is a sensory overload, let’s see what that is and take it away.”

Joshua was nonverbal until he was 6. He learned to speak after Juliet labeled everything in the house and read the label every time Joshua used it. If she gave him a glass of water, she said, “water.” If she opened a door, she said, “door.”

“One day, Josh said ‘waaa’ meaning water,” Juliet said. “And waa eventually became ‘water.’ And I was like, ‘He can speak!’”

He said his first full sentence when he was 9:“Water, please.”

When asked what he likes about his school, Joshua said, “I have friends.”

When asked what he would like to do after he graduates, he said get a job at the airport as a “plane spotter.” He can look in the sky and tell you the type of plane flying into nearby Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport. Juliet said she will look into an internship for Joshua at the airport but knows he will need tight supervision, since he tends to get distracted. He will never live on his own, but Juliet is hopefully he can live in a supervised group home.

Still, she never envisioned Joshua would progress this far 10 years ago when she began Dickens Sanomi Academy as, she said, a last resort to give her son an education.

“No, because I had all these limitations put in front of me by the system,” she said. “I was told all these things he couldn’t do, and in the back of my mind I was trying to believe so hard that he could do a lot.”

Turns out those constraints disappeared once Juliet learned a way around them. That’s her goal for all her students who are on the spectrum.

“The children are the drivers of the ship,” she said. “They show us what they’re capable of, what to put in place, how to help them. It’s a learning environment for all, the teachers, even myself. It’s taken a village to actually raise them, and it will take a village to continue.

“I wish the world knew what it has with these kids.”

Roger Mooney, manager, communications, can be reached at [email protected].